[Content note: brief, non-graphic mentions of domestic violence, transphobic violence, discrimination, harassment]

The Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF) organisation Women’s Place UK recently launched to campaign against proposed reforms to the Gender Recognition Act (GRA). These reforms would include changing the way in which a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) would be issued. A GRC allows a transgender person to have the gender marker on their birth certificate changed to match their identified gender, as opposed to the one assigned to them at birth. It does not affect a person’s ability to have their gender changed on most forms of ID, to access most services or to present however they wish. The current process is onerous and expensive, involving the submission of medical reports and various kinds of evidence to a Gender Recognition Panel, who you will never meet face to face, and a £140 fee. The proposed reform instead suggests adopting a system similar to that which has existed, without serious problems or evidence of large scale abuse, in Ireland for the last 2 years, wherein receiving legal recognition of identified gender is a matter of simply filling out a form.

Women’s Place UK has issued “five simple demands” via their social media. In this article, I want to focus on the fifth of these demands – “The government to consult on how self-declaration will impact data-gathering and the monitoring of discrimination.“ Given that the first of their demands is for a “respectful and evidence based discussion” and I have some relevant experience as a postgrad researcher specialising in statistical modelling, I felt that I could speak to the likelihood that the proposed reforms would have any detrimental effect on the monitoring of gender discrimination.

The first question to ask is whether the proposed changes would, in fact, alter the collection of data on discrimination at all. How is this data gathered? Often demographic data is obtained by self-reported questionnaires, in such data a person’s gender quite literally reflects which box they ticked. Whether trans people will typically wait until after they have obtained a GRC to accurately report their gender in data or simply tick whatever box they please I leave as an exercise for the reader. Sometimes data is instead gathered based on pre-existing gender markers on databases (e.g. the NHS database), as with the process of obtaining a passport with a new gender marker or accessing most sex specific services, this does not require a GRC and can usually be arranged by presenting a letter from a doctor or other health care professional stating that the individual concerned has gender dysphoria. In other words, as far as “data gathering and the monitoring of discrimination” are concerned we already effectively have self-identification.

Next, it is instructive to consider the likelihood that trans people self-identifying in survey data (as is already the case) would actually mask any meaningful statistical effects with respect to discrimination. There are two reasons that I would consider this to be unlikely; the small number of trans people in the general population and the reality of trans experience.

Estimates for the number of trans people in the population varying depending on method, studies using self identification (which would, of course, be the most relevant here) tend to find prevalence in Western populations between 0.1% (1 in 1,000) and 0.5% (1 in 200) and a 2016 systematic review found a 95% confidence interval for self reported transgender identity of 0.144%-0.566% with a mean of 0.355%. For perspective this would amount to, at worst, a rounding error for descriptive statistics given to the nearest percentage point, hardly likely to interfere in any serious way with data-gathering.

But what of more sophisticated, inferential statistical methods? What if there were some effect dependent entirely on assigned at birth gender, such as increased likelihood of some negative outcome for people assigned female at birth (AFAB), which went undetected by statistical investigation due to transgender self-identification? This is also somewhat unlikely and in the spirit of a respectful and evidence based discussion, I will attempt to demonstrate so empirically. We can model such a scenario and compare the ability of a standard statistical method used in social sciences (in this case the Chi-Squared test for independence) to detect a meaningful difference in an outcome for AFAB and AMAB individuals both without and in the presence of transgender self identification.

As always in statistical modelling (and particularly while carrying out simulations), we should be clear in the assumptions that we are making. Some of the assumptions I will make are, in reality, not entirely true, but match with the reality implied by trans exclusionary organisations’ stated concerns:

- Effects based on gender are determined entirely by the gender a person is assigned at birth, such that a trans woman and a cis man will have the same or very similar outcomes (I will demonstrate that this is simply untrue later in the article, but will allow for such an assumption for modelling purposes)

- 0.5% of the population will be transgender, identifying as other than the gender they were assigned at birth (this is perhaps an overestimate, but sits at the upper bound of plausible figures).

- We can reasonably represent transgender individuals by changing a binary gender marker (this is not strictly true, and may be understandably contentious for non-binary individuals, but reflects the binary thinking prevalent in trans exclusionary discourse, which this simulation aims to reflect in its assumptions)

- AMAB and AFAB individuals are equally likely to be transgender.

- The outcome of interest occurs at a rate of 4% for AMAB individuals and 8.2% for AFAB individuals (this was chosen to reflect the real life statistic of annual risk of domestic abuse for men and women in England and Wales, source for this statistic here)

The procedure for the simulation was carried out as follows:

- For sample sizes N=[50, 100, 500, 1000, 1,500, …, 10,000]:

-

- Let G be a variable representing assigned at birth (AAB) gender, sample N cases from a binary uniform distribution (0 = AMAB, 1 = AFAB)

- Let O be the outcome of interest

- For each value in G, G(i):

-

- Sample a random number from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1, R

- If (G(i) = 0 AND R < 0.04) OR (G(i) = 1 AND R < 0.082):

-

- O(i) = 1

- Else:

-

- G(i) = 0

- Use a chi-squared test with alpha = 0.05 to test whether G and O are independent. If test indicates independence, record as a false negative

- For each value in G, G(i):

-

- Sample a random number from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1, R

- If R<0.005, G(i) = 1 – G(i)

- Use a chi-squared test with alpha = 0.05 to test whether G and O are independent. If test indicates independence, record as a false negative

- Repeat steps 1.1-1.7 1,000 times

Matlab code for this procedure can be provided upon request and I welcome any attempts to replicate this small experiment.

Addendum 8/12/17: It’s been pointed out to me that the way that I have explained parts of this is a touch opaque. It’s not my intention to blind anybody with science with this piece so, a brief sidebar on the Chi-Squared test and exactly what I have done here.

The Chi-Squared test is a standard statistical method used to test whether two categorical variables are independent of each other. So say you have people belonging to groups A and B and they can also belong to groups X and Y, and you want to know whether membership of group A or B affects probability of being in group X or Y, you might use a Chi-Squared test to determine this.

E.g. you have a sample of cats and dogs and they are all named either Fido or Felix and you want to determine whether being a cat or a dog affects how likely an animal is to have either name. You could look at raw numbers and see that, say, 70% of cats are named Felix vs. 1% of dogs (this would be descriptive statistics), you would use a statistical test like Chi-Squared to work out the probability that you’d get those numbers by pure chance (a p-value), the lower the p-value the more sure you can be that there’s a real effect going on, quite literally asking yourself “Well what are the chances of that?” A p-value of 0.05 (5% or 1 in 20) is often used as the cut off point at which we say a result is “statistically significant”.

In straightforward terms, what I have done is generated data simulating a scenario matching the assumptions I have laid out above and applied the Chi-Squared test many times, each time both with and without allowing for self-identification of gender. For each sample size (number of hypothetical people in each simulated test) I have recorded the number of times that the test failed to detect the presence of a link between gender and our outcome of interest.

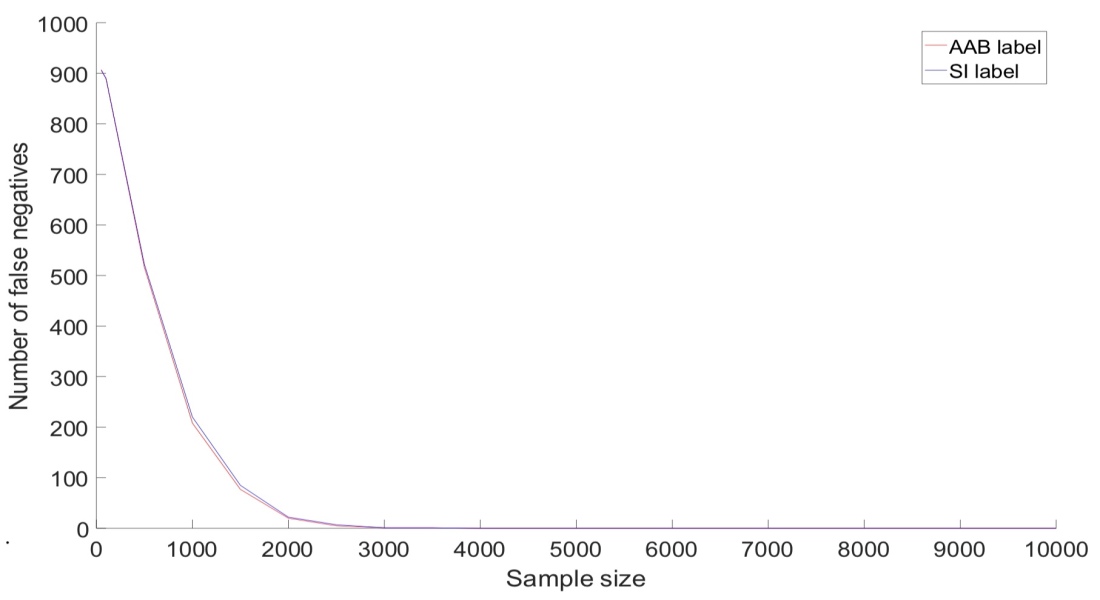

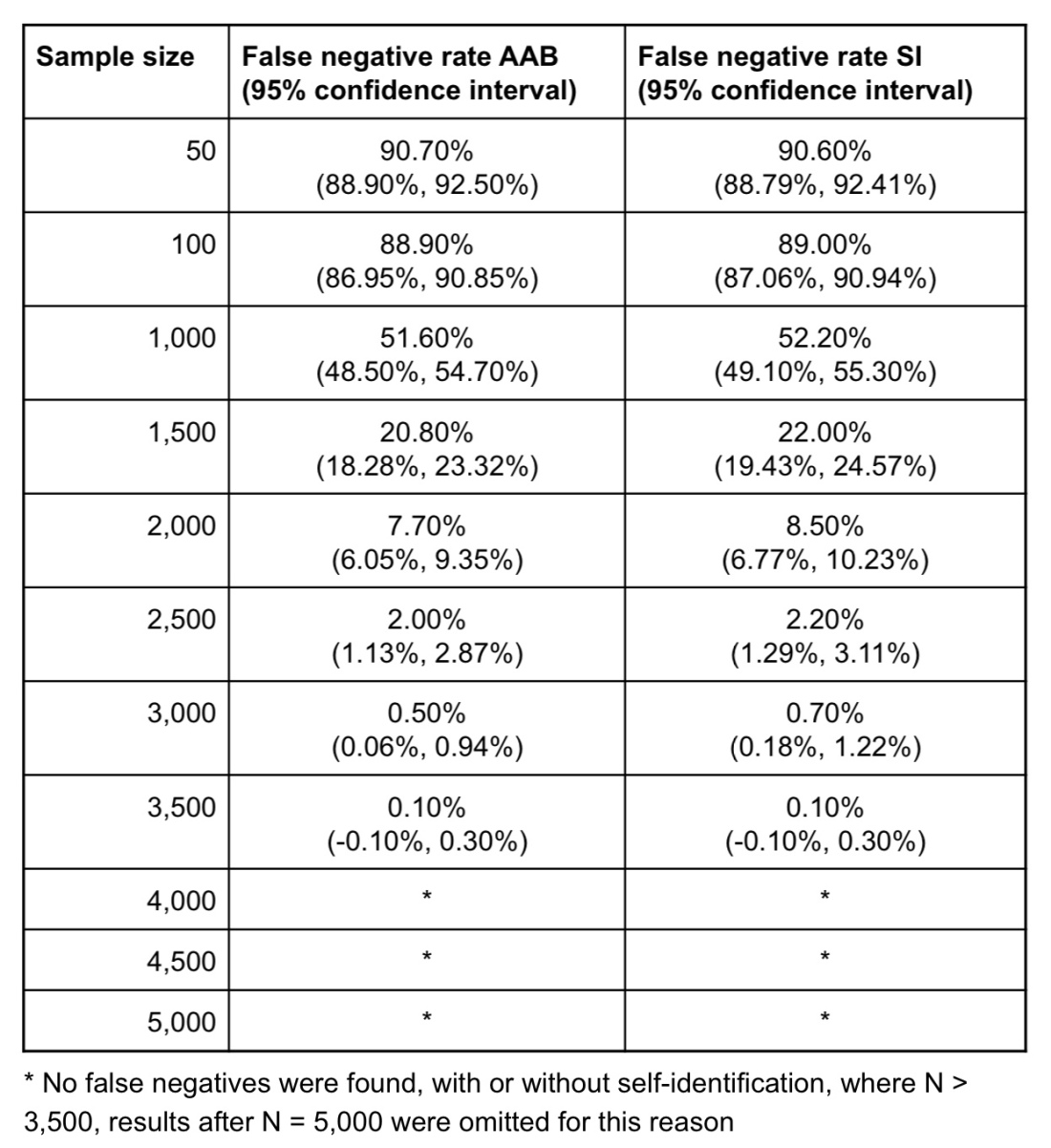

Having done this, we can compare the rate of false negatives with and without transgender self-identification. As shown in the figure and table below. Broadly speaking, there is no evidence of a statistically significant difference in false negative rate using AAB and SI gender under the assumptions of this simulation. For samples of size 4,000 or greater, no false negatives whatsoever occurred under either method. The introduction of such a small amount of noise to the data simply does not seriously affect the ability of statistical methods to detect meaningful statistical effects.

Having established that self-identified gender is the status quo for data gathering on discrimination and that it is unlikely to have a detrimental effect on that data gathering in any case, it is also salient to question the underlying assumption implied by the demands made by Women’s Place UK and similar organisations; that gendered outcomes are strictly determined by AAB gender. TERF organisations fear trans women being recorded in statistics on discrimination as women because they assume that that transgender women will have similar outcomes to cisgender men and will thus skew the data and mask discrimination. The reality, of course, is that trans women (and trans people in general) are a marginalised group who experience significantly worse outcomes in several major areas relative to cis people.

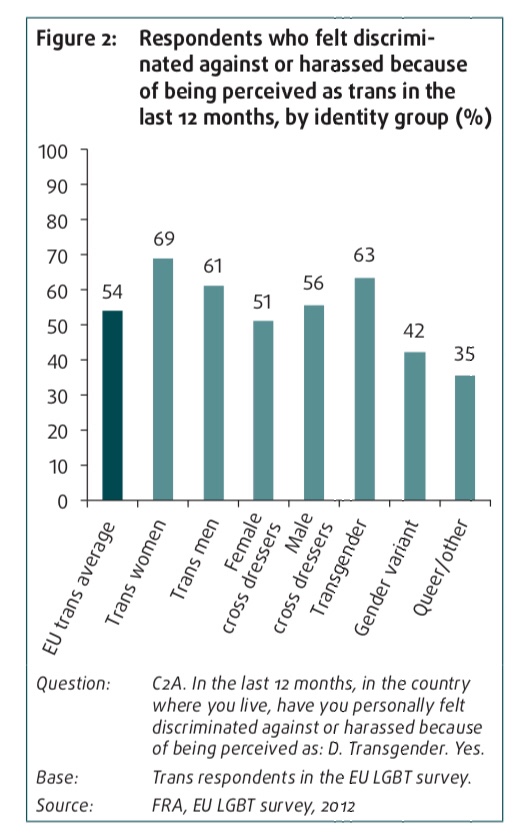

A 2015 EU report on trans experience in the EU found that “trans people face frequent infringements of their fundamental rights: discrimination, violence and harassment” and were more likely on average to be in the bottom 25% of earners. Around half of trans respondents reported being harassed or discriminated against in the last year, with this rising to 7 out of 10 trans women (see the graphic, taken from the report, below). A little over a third reported discrimination in finding housing and another third reporting discrimination at work. One in seven trans people and one in six trans women reported experiencing violence or threats of violence in the 12 months before the survey.

A 2007 equalities review by Press For Change and Manchester Metropolitan university had similarly grim findings, reporting both discrimination both economic and social, with a third of trans people being excluded from family events and/or having family members break all contact with them and a fifth experiencing isolation within their community (page 17).

Housing and workplace discrimination, violence, alienation from family and isolation within the wider community. These are common themes when both examining statistics on trans people and when listening to the anecdotal experiences of trans people. The idea that, even if it were somehow impossible to account for whether people were trans within survey data by simply asking, the inclusion of such a group within any larger demographic could serve to hide discrimination against that larger group is simply absurd.

So to return to Women’s Place UK’s demand for a “respectful and evidence based discussion” in the area of data-gathering and the monitoring of discrimination; from an evidence-based perspective, there is, respectfully, no basis whatsoever to any suggestion that making the process of obtaining a GRC less bureaucratic, expensive and invasive could in any way hamper data-gathering or the monitoring of discrimination.

Reblogged this on Wessex Solidarity and commented:

There are many angles from which to approach this issue and come to the same conclusion. I like “an injury to one is an injury to all” but this is for people who like maths. Mal C.

LikeLiked by 1 person